This is an 'adultified' and slightly enhanced version of a talk I gave to Siddington Church of England Primary School

on 8/05/2025 to mark the eightieth anniversary of

VE Day : May 2025

I was born in July 1932. I’ve been very lucky to have lasted as long as I have. War had begun in September 1939 and had lasted into part of 1945, so that was five years and seven months. At the start of the war I was just over seven years old, and when it finished in Europe I was almost thirteen years old.

What follows are some of my memories of what it was like to be a school child living through a war. Again, I must say I was very lucky – my father had served in the Air Force in the First World War and so was too old to have been called up for military service and we were able to continue as a family unit. Also, where we lived was residential and well away from any city centre or airfield or important factory and so not a priority target for bombing raids.

But we did hear the dull drone of fleets of big German aircraft coming over, mostly early at night, to drop high explosive bombs on London and elsewhere to cause as much damage as possible, sometimes with incendiary bombs to set things on fire too. Unfortunately, you’ll have seen the kinds of damage they cause, like the television news pictures from Ukraine and Gaza.

The difference in those days years ago was that instead of using a few missiles, each guided to a particular target, hundreds of bombs were simply dropped from a great height, almost at random, over target areas. At one time I was living with my grandparents fairly high on the North Downs hills south of London and we could see the centre of London, fifteen miles away, lit up by night-time fires. As I said, I was much more fortunate, not suffering anything like that.

Indeed, my big sister and I were living fairly normal lives during most of those war years. We went to school as usual – by bus or by bike (no ordinary folk had any petrol for running cars, only doctors, vets and farmers and the likes had permits for petrol). Although the heavy bombing was mostly at night there were some day-time raids and visits by German spy aircraft. So the air-raid sirens might sound out in school hours and we’d break off whatever we were doing, collect our coats and go down to whichever of the outside underground shelters our form had been allocated. When I say underground I don’t mean they were dug down like underground trains: trenches had been dug out in the school playingfield just a few feet deep, with corrugated iron structures built in the trenches and all the spare soil heaped on top – just leaving some steps down at one end of each. They couldn’t save anyone from a bomb, but there were no hundreds of tons of bricks and rubble to trap us as happened when a school or any big building was hit or damaged.

On a smaller scale, ordinary houses – like ours and millions of others – could have their own shelters. If a garden was available this could be an Anderson Shelter, like a six-foot version of the school shelter. My grandparents had one, so during the worst of the 1940 London Blitz we all squeezed into the bench seats and played cards and other games from about eight o’clock in the evening until the all-clear sounded at perhaps 10.30 or eleven. Then up to bed as normal.

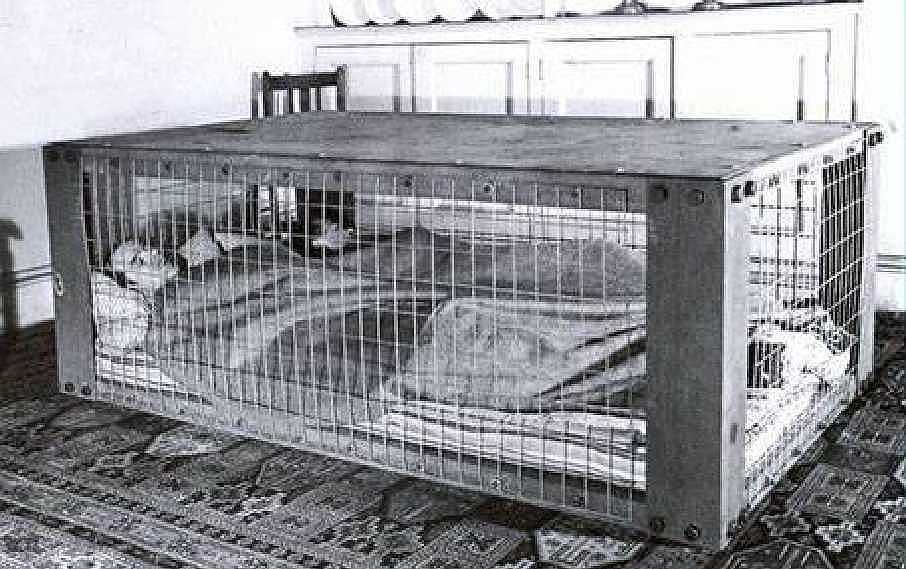

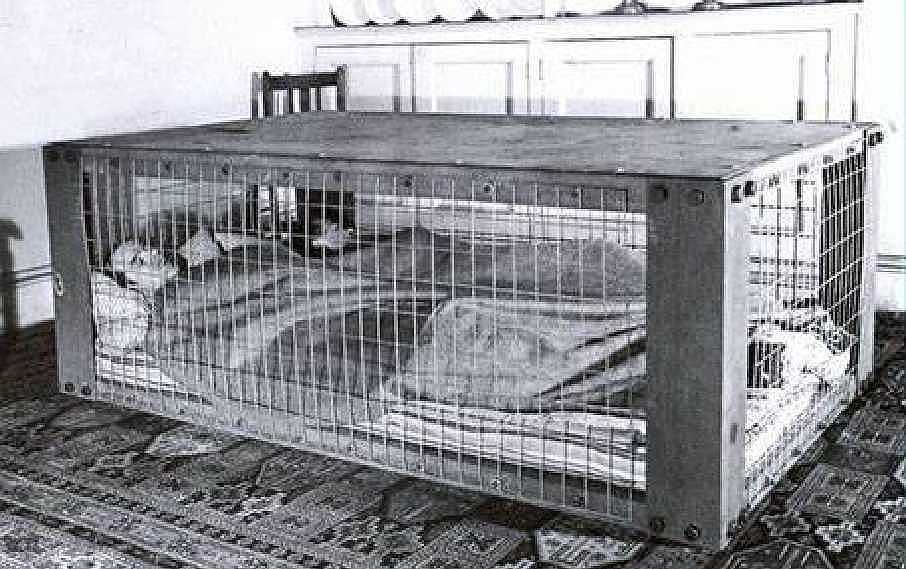

Later on, in our own home, we opted for an indoor shelter which was like a heavy dining table made of steel, with steel mesh sides. It was possible to sleep under it – as well as using it AS a dining table. It was known as a Morrison Shelter.

Coming back to ordinary living – most foods were rationed, including butter, lard and margarine, sugar, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, bacon, eggs (one each per week, I think), tea, and even sweets – something like two Mars bars per MONTH. All forms of meat were rationed other than liver and kidneys, but long queues formed for those when it was known there might be a delivery. Bread was not rationed during the war itself, but there was only one kind – a sort of wholemeal – large loaf or small loaf. Teatime was mainly bread with butter OR margarine OR jam, and if they had already run out there was some almost tasteless jam and meat paste substitutes. For special occasions there MIGHT be some golden syrup - sixteen ration 'Points' a two-pound tin! There were no imported fruits of any kind. I don’t remember having oranges or bananas until well after the war, when I was about 15. Milk and home-grown vegetables could not be rationed because the government could not guarantee to provide regular supplies. But we lived close to a United Dairies depot so I don’t remember us going short of milk – it was delivered early each morning by horse and cart. To be fair, my sister and I didn’t have to worry about much of this: it was housewives like our Mum who had to try and make tasty meals out of very limited supplies. Again, we were lucky in that some waste land opposite our house was turned into allotments: Mum got half of one and was able to grow some vegetables there.

What my sister and I DID get concerned by was clothes rationing. We were both getting bigger and growing out of our clothes. But buttons could be moved - some seams could be let down. It was much more difficult with shoes: in fact my small toes still curl under my other toes because there wasn’t room for them to grow normally in the only shoes I had available at one stage as a teenager.

Which reminds me to mention that although VE – Victory in Europe – came in 1945 rationing in one form or another – even including bread at one stage – continued for another SEVEN years – longer than the war had been – finally ending in June 1952. (All this rationing made children MORE healthy – no stuffing sweets, no over-eating puddings, plus plenty of exercise getting to school, so nobody ever heard of obesity!)

The Germans failed with their 1940 bombing campaign and the British Spitfires and Hurricanes won the Battle of Britain, so the Germans never could even attempt to invade any part of Britain other than the Channel Islands. But they did march into Poland, France, Russia and most other parts of central Europe as well as some deserts in North Africa. The Germans were being helped by the Italians, but by 1943 things were not going well for them – they were too busy elsewhere to worry about sending bombers to have another go at Britain. So there were very few air raids and we just carried on with normal life as well as we could.

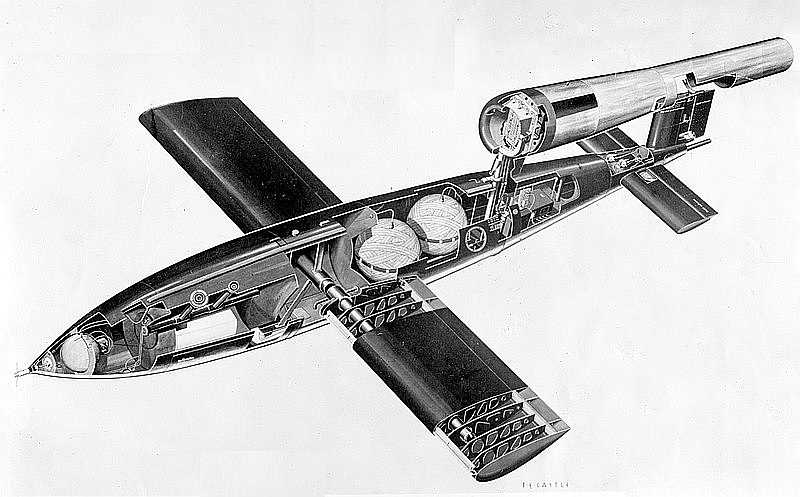

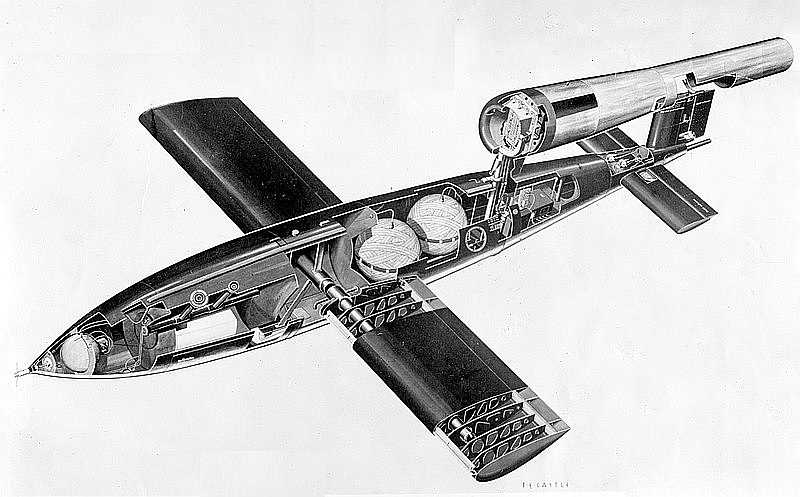

But the German scientists had been developing totally new missiles - bombs that didn’t need to be dropped from aircraft at all. The so-called V1 or Doodlebug machine was a bomb shaped like a fat tube with short wings plus a small jet engine mounted on top.

Each one was launched from the other side of the English Channel, pointing towards London though it could not be reliably controlled once it was flying. When it ran out of fuel the engine stopped, the bomb might glide on for a mile or two but then fell and exploded wherever it happened to be. The Germans planned that that should be central London. They sent something like ten thousand of them over, to frighten all the folk living in the area, as a psychological terror weapon rather than for targeted destruction. That was called the Doodlebug Blitz which began in the summer of 1944 soon after my twelfth birthday. These bombs were sent over mainly in the daytime, just a few at a time, so the air raid warnings sounded on and off for short periods or long. Each doodlebug engine made a throaty sort of roaring sound – and that was fine: if the engine was still going it wasn’t going to land on you. But if you heard the engine cut out or, worse still, if you spotted a silent one gliding you could only pray and take whatever cover was available. [You can see masses of details on Wikipedia.]

During the bomb blitz of 1940 many parents of children in town centres and other target areas could have their children evacuated. The children were put on trains specially organised to take them away to stay with host families on farms and in villages in much safer areas for months or even years. Some could even be sent – without their parents – to Canada, by boat across the Atlantic, itself a risky process. None of these affected our family, but the doodlebug blitz wasn’t confined to particular areas: the bombs could land anywhere in south-east England. So although we ought not to miss too much school time, Mum and Dad decided that my sister and I should spend the summer of 1944 far away, staying with some distant relatives who had agreed to take us, in a country cottage in a village near Hereford. That was the first long train journey my sister and I had ever had – all pre-war holidays had been by car. I must say, we had a lovely summer exploring the fields, walking along to the farm for milk and to buy tomatoes.

Not so for our Mum. I said that she had an allotment opposite the house. One morning a doodlebug landed on it causing a lot of damage to our house and many nearby buildings. Fortunately there had been a warning and Mum had been indoors and was safe, uninjured. Dad was away at work. Of course by 1944 everyone knew what to do. The local council came round and inspected. The house was still upright but, like our neighbour's, too badly damaged to be lived in. Removal lorries and teams of volunteers came and loaded all the furniture and everything else from knives and forks to sacks of coal. The family was allocated half of a country house in the next village, to be shared with our next-door neighbours.

(I may add that our neighbour’s house was repaired much later. Ours was pulled down, just leaving the central wall we shared with that neighbour and our bare foundations. It was rebuilt quite soon after the war so my sister and I were still teenagers when we were able to move back to that house. We had been looking after the back garden in between times, though we had to make a new front garden when the builders had finished. I can’t show you any photos. Photos used to need films in cameras in those days, and they weren’t available to the general public in wartime.)

Anyway, about our new half-house home in the next village …

That had had a proper garden but it had grown over with wild plants after years with the house just used as Fire Service offices and garage. And not only a wild garden – there was a small wild field too, AND quite an interesting strip of woodland along a steep bank: it was wonderful. What wasn’t so good was that there was no bus service back to where we had come from. So my journey to secondary school involved a 2.9-mile bike ride down into the valley and up the other side – with lights in the winter months – leaving the bike in the grocery shop’s back store and catching the original bus another three miles to my school in town. In all weathers! And back in the late afternoons!! With no extra rations for all that effort!!!

We didn’t totally escape the war in our new home. After the V1 doodlebugs the German scientists designed the V2 Rockets. These were the first fully developed huge rockets that could fly right up to the edge of space and again, like the V1s come back to earth – somewhere in south-east England – when they ran out of fuel. [Details on Wikipedia.] Coming down from such a great height they were travelling faster than sound. So with no possible warning of any kind you heard the bomb-head explode and THEN you heard it coming! Fortunately there weren’t a lot of them [1,400], not like the doodlebugs, but one did land in a field about half a mile from our new home. It didn’t kill anyone or anything – just made a crater in the ground, in the chalk.

We didn’t totally escape the war in our new home. After the V1 doodlebugs the German scientists designed the V2 Rockets. These were the first fully developed huge rockets that could fly right up to the edge of space and again, like the V1s come back to earth – somewhere in south-east England – when they ran out of fuel. [Details on Wikipedia.] Coming down from such a great height they were travelling faster than sound. So with no possible warning of any kind you heard the bomb-head explode and THEN you heard it coming! Fortunately there weren’t a lot of them [1,400], not like the doodlebugs, but one did land in a field about half a mile from our new home. It didn’t kill anyone or anything – just made a crater in the ground, in the chalk.

I don’t have any special memories of VE day. Perhaps I was too busy with my school exams at the time. In any case, the ending of the war in Europe made no difference whatever to the rationing of food, petrol, clothes and so on: as I’ve said, food rationing went on for another seven years. Some things did get easier straight away though. There was no longer any night-time blackout so extra black curtains could be thrown away; masks could be taken off bus, lorry, van and car headlights; public bomb shelters could be changed back to something useful at last, and home shelters dismantled.

But there was still our equally terrible war against the Japanese, half a world away. That didn’t end for another three months after our new, ghastly atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki proved that they could not win. VJ Day, Victory over Japan Day, was officially celebrated on 15th of August that same year, 1945.

Then the second world war really was over.

<<<<<<<<<<+>>>>>>>>>>

Our house: SM7 2DW

Grandpa's house: SM2 5JA

Our shared country house: CR5 3PT

Evacuated to HR4 7RE

We didn’t totally escape the war in our new home. After the V1 doodlebugs the German scientists designed the V2 Rockets. These were the first fully developed huge rockets that could fly right up to the edge of space and again, like the V1s come back to earth – somewhere in south-east England – when they ran out of fuel. [Details on Wikipedia.] Coming down from such a great height they were travelling faster than sound. So with no possible warning of any kind you heard the bomb-head explode and THEN you heard it coming! Fortunately there weren’t a lot of them [1,400], not like the doodlebugs, but one did land in a field about half a mile from our new home. It didn’t kill anyone or anything – just made a crater in the ground, in the chalk.

We didn’t totally escape the war in our new home. After the V1 doodlebugs the German scientists designed the V2 Rockets. These were the first fully developed huge rockets that could fly right up to the edge of space and again, like the V1s come back to earth – somewhere in south-east England – when they ran out of fuel. [Details on Wikipedia.] Coming down from such a great height they were travelling faster than sound. So with no possible warning of any kind you heard the bomb-head explode and THEN you heard it coming! Fortunately there weren’t a lot of them [1,400], not like the doodlebugs, but one did land in a field about half a mile from our new home. It didn’t kill anyone or anything – just made a crater in the ground, in the chalk.